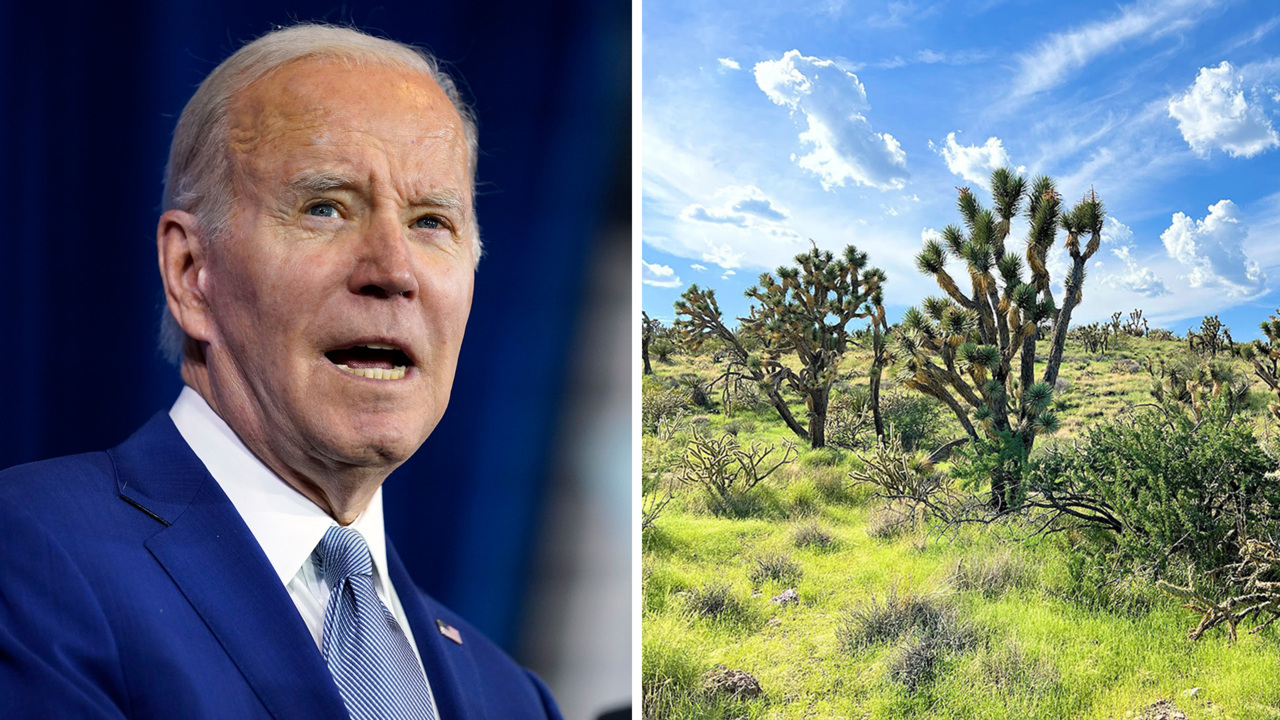

The White House announcement that President Joe Biden on Tuesday will designate two long-sought-after national monuments in Nevada and Texas drew widespread praise from Native American tribal leaders, residents and conservation groups.

But it also raised questions about how the Biden administration will protect the sites and allow them to be fully enjoyed by the public.

What is clear is that the moves rank among the largest conservation initiatives undertaken by any administration in decades (Greenwire, March 21).

The centerpiece is arguably the Avi Kwa Ame National Monument, which will permanently protect 506,814 acres of federal lands considered sacred to Yuman-speaking Native American tribes in southern Nevada and serve as a connecting point between the Mojave National Preserve and the Castle Mountains National Monument to the west, in California, with the Lake Mead National Recreation Area to the east in Nevada.

Biden announces new national monuments in Texas, Nevada

lead image

lead image

While Biden vowed last year to protect that Nevada site, the announcement that the president will also designate the Castner Range National Monument in West Texas was unexpected, even as it strikes a core administration goal to increase access to parks and open spaces to marginalized communities. Biden will announce the monuments at an event Tuesday afternoon at the Interior Department.

To the residents of El Paso, especially in the poorer northern end of the city who have pushed for decades to preserve the old Army training grounds that are now renowned for the annual bloom of Mexican gold poppies each spring, the 6,672 acres are a valuable open-air space that connects to the eastern slope of the Franklin Mountains.

“I’m absolutely thrilled about the designation,” said Rep. Veronica Escobar (D-Texas), who in 2021 sponsored legislation that, if successful, would have established the national monument. “It brings me such joy to know that El Pasoans will soon be able to enjoy the beauty of this majestic, expansive landmark for years to come.”

Now comes the hard part.

Despite the designation of Castner Range National Monument on Tuesday as the third national monument in Texas, the former Army artillery range and training grounds remain, as they have for decades, closed to the public.

When people will actually be able to walk and recreate on the monument is an open question.

Though the Army stopped using Castner Range in 1966, its legacy of decades of use as a military training ground, beginning in 1926, have left it littered with unexploded artillery.

If you want to see the Mexican gold poppy blooms that carpet the desert floor at the site each spring, you need to walk along a 1-mile trail at the El Paso Museum of Archeology on the perimeter of the site.

And while supporters of designating Castner Range a national monument say its establishment provides disadvantaged communities in El Paso with much-needed recreational benefits, those also won’t be realized until it is made safe to visit.

The monument area is part of the Fort Bliss and will be managed by the Army.

Undersecretary of the Army Gabe Camarillo, who is an El Paso native, visited the Castner Range area last August and pledged to complete cleanup of unexploded ordnance there.

Camarillo said in a Tuesday statement that while Castner Range “has been an indelible part of U.S. Army history,” he added that “now it’s time to write a new chapter about the future of this natural treasure.”

He added: “Moving forward, the U.S. Army stands ready to execute a complete clean up, manage remaining munitions and make Castner Range safe for public access.”

As it stands today, little is known about what wildlife and plant species reside there, as well as the archeological resources.

National monument proponents say that as many as 27 wildlife or plant species that the Fish and Wildlife Service have listed for protection under the Endangered Species Act are present on the Castner Range site. Those include the ferruginous hawk, the Texas horned lizard, and the Franklin Mountains talus snail, among others.

The site in the Chihuahuan Desert also includes archaeological resources showing evidence of human habitation dating back 10,000 years, when according to a White House fact sheet the area was home to the Apache and Pueblo peoples and the Comanche Nation, the Hopi Tribe and the Kiowa Tribe of Oklahoma.

“Now we can get the real work of interpretation and narrative around Castner Range, providing access and context at the same time,” said Eric Pearson, president and CEO of the El Paso Community Foundation, which helped spearhead local efforts to get the new monument.

An expanded Nevada monument

The Avi Kwa Ame National Monument will be slightly larger than what had been originally proposed by advocates and Rep. Dina Titus (D-Nev.) in legislation she sponsored last year to establish the monument that stalled.

The initial proposal for the Avi Kwa Ame National Monument called for preserving roughly 450,000 acres of BLM-managed lands, but White House press materials indicate it will include at least some Bureau of Reclamation and National Park Service lands, as well, increasing the size of the monument to 506,814 acres by adding parcels in the Lake Mead National Recreation Area.

“President Biden’s establishment of Avi Kwa Ame National Monument is a testimony to protecting and preserving lands with not just our children and grandchildren in mind but for generations to come,” Theresa Pierno, president and CEO of the National Parks Conservation Association, said in a statement.

Biden pledged to protect the area during a speech at the White House Tribal Nations Summit in Washington last year, saying he understood that it is a “sacred place that is central to the creation story of so many tribes” (Greenwire, Nov. 30, 2022).

The Avi Kwa Ame National Monument will protect biologically diverse and culturally significant lands in the Mojave Desert. Straddling the Nevada-California border, it’s nestled between the Mojave National Preserve; the Castle Mountains and Mojave Trails national monuments in California; and the Lake Mead National Recreation Area and four wilderness areas on the Nevada side of the border, including the Spirit Mountain Wilderness Area outside the eastern boundary of the monument that’s home to the region’s 5,600-foot-tall namesake peak.

“The president’s action today will safeguard hundreds of thousands of acres of cultural sites, desert habitats, and natural resources in southern Nevada, which bear great cultural, ecological, and economic significance to our state,” the Honor Avi Kwa Ame coalition comprised of Native American tribal leaders, local government officials, conservation groups and residents said in a statement.

The Interior Department will enter into a memorandum of understanding to manage the new monument in cooperation with tribal nations that consider the lands along the Nevada-California border sacred, including the Fort Mojave Indian Tribe and nearly a dozen others in Nevada and Arizona, the White House said. However, the presidential proclamation says that the Bureau of Land Management will have “primary management authority” over sections of the landscape it already controls, and the National Park Service will have primary oversight of sections of the new monument that include Lake Mead NRA.

“Together, we will honor Avi Kwa Ame today — from its rich Indigenous history, to its vast and diverse plant and wildlife, to the outdoor recreation opportunities created for local cities and towns in southern Nevada by a new gorgeous monument right in their backyard,” the coalition said.

The need to protect the Avi Kwa Ame site has been underscored the past few years by strong interest from renewable energy developers.

For example, a solar energy developer had proposed a commercial-scale project on more than 2,500 acres of BLM lands, including 2,000 that were inside the proposed monument boundary.

The White House said Tuesday that the Avi Kwa Ame National Monument designation “will not slow the positive momentum of clean energy development in the State of Nevada,” where BLM is processing roughly 36 renewable energy applications for projects with a capacity to produce 13,000 megawatts of electricity, or enough to power about 4 million homes.

Massive Pacific Islands sanctuary?

Biden on Tuesday will also sign a presidential memorandum directing Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo to evaluate using her authority under the National Marine Sanctuaries Act to designate a marine sanctuary covering an enormous 777,000 square miles — including the existing Pacific Remote Islands Marine National Monument, southwest of Hawaii — within the next 30 days.

A new marine sanctuary at that size would allow the Biden administration to reach the goal outlined in the “America the Beautiful” initiative to conserve 30 percent of the nation’s waters by 2030, the White House said.

The White House said Tuesday that the vast area of the Pacific Ocean would encompass “all areas of U.S. jurisdiction around the islands, atolls, and reef of the Pacific Remote Islands,” protecting a region that “has a rich ancestral tie to many Native Hawaiian and Pacific Island communities.”

In addition, the review of the area for possible designation “would allow the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to further explore the area’s scientific, cultural, and ancestral linkages, and tailor its management accordingly,” according to a White House fact sheet.

The process to explore a possible sanctuary designation will also include Raimondo working with Interior Secretary Deb Haaland to “conduct a public process to work with regional Indigenous cultural leaders to appropriately rename the existing Pacific Remote Islands National Monument, and potentially the Islands themselves, to honor the area’s heritage, ancestral pathways, and stopping points for Pacific Island voyagers,” the fact sheet said.

Environmental groups were largely pleased with Tuesday’s announcements, which in addition to the two national monuments and possible marine sanctuary also are expected to include new initiatives on tapping the ocean for renewable energy and committing federal land management agencies to incorporate establishing wildlife mitigation corridors and other measures into land-use planning.

But they were also stung by Interior’s approval last week of the massive Willow oil and gas project in the Alaskan Arctic. The administration has defended the move, saying that Interior didn’t have leeway to void oil company ConocoPhillips’ leases (Greenwire, March 17).

“I’m glad to see President Biden taking these modest but important steps for conservation, but his actions on fossil fuels still leave us in a deep hole,” said Randi Spivak, public lands program director for the Center for Biological Diversity. “As the climate crisis accelerates and unravels our planet’s biodiversity, it’s clear we can no longer afford to stroll toward solutions. It’s time for the Biden administration to start sprinting.”